What impact might Brexit have on UK taxation?

12 Aug 2016It’s unlikely to have escaped anyone’s attention that a political and economic storm has descended upon Britain post-Brexit, and (like the rest of the electorate) small business owners are uncertain about what it will mean for taxation.

George Osborne, the current Chancellor of the Exchequer (although how long he can remain in that role is anyone’s guess), has warned that the UK’s decision to leave the EU will mean tax rises and spending cuts. That probably goes without saying, but he’s said it anyway.

However, during the referendum campaign Osborne was rather more pointed, unveiling an emergency budget that detailed the £30 billion raft of budget cuts and tax hikes he might use to tackle any fiscal black hole caused by a Leave vote. Following the referendum result Osborne has changed tactics and put that emergency budget on hold for now, but there is little doubt that in the months and years ahead Britain’s tax legislation, much of which is informed by and intertwined with EU directives, will have to be revised.

While it’s important to point out that nothing is certain at this stage, let’s take a look at how small business taxes might change as Britain negotiates its exit from the European Union.

Brexit Business rates

Business rates, or ‘National Non-Domestic Rates’ to use their full name, are taxes levied on business property. They are not derived from EU legislation, and are set at a rate decided by the British government and calculated against property valuations that are determined by the UK’s Valuation Office Agency.

Considering these commercial property taxes are entirely domestic, and small businesses already benefited from a substantial £6.7 billion cut to business rates just a few months ago during Osborne’s Budget 2016, it’s unlikely they will fall further anytime soon.

In fact, in the wake of the Brexit vote it is possible small businesses may see business rates go back up again, as the heads of local council authorities are now calling for the £6.7 billion cut to be reversed in order to balance out an expected decline in public sector funding.

Brexit Corporation Tax

Company tax rates in the EU have not been harmonised, and each member country determines its own rate of Corporation Tax, which currently stands at 20% in Britain.

However, one aspect of Corporation Tax in the UK could be affected by Brexit. In 2015 the British government introduced the Corporation Tax (Northern Ireland) Bill, which provides for the devolution of tax powers to the Northern Ireland Assembly, empowering the Assembly to set its own ‘Northern Ireland Rate’ of Corporation Tax.

The Assembly is expected to introduce a rate of 12.5% in 2018, in line with the rate in the Republic of Ireland, but this move was expected to come with a caveat - in order to ensure it doesn’t breach the EU’s state aid rules the reduction in revenue that results from a lower Northern Ireland Rate would need to be offset by an equal reduction in Northern Ireland’s regional budget.

When the UK leaves the EU those restrictions on state aid may no longer apply, so in theory the British government could be free to allow Northern Ireland to lower its Corporation Tax rate without a similar reduction in the province’s annual budget, and the Welsh Assembly and Scottish Parliament could potentially follow suit with their own devolved Corporation Tax rates (assuming Scotland remains part of the UK, of course).

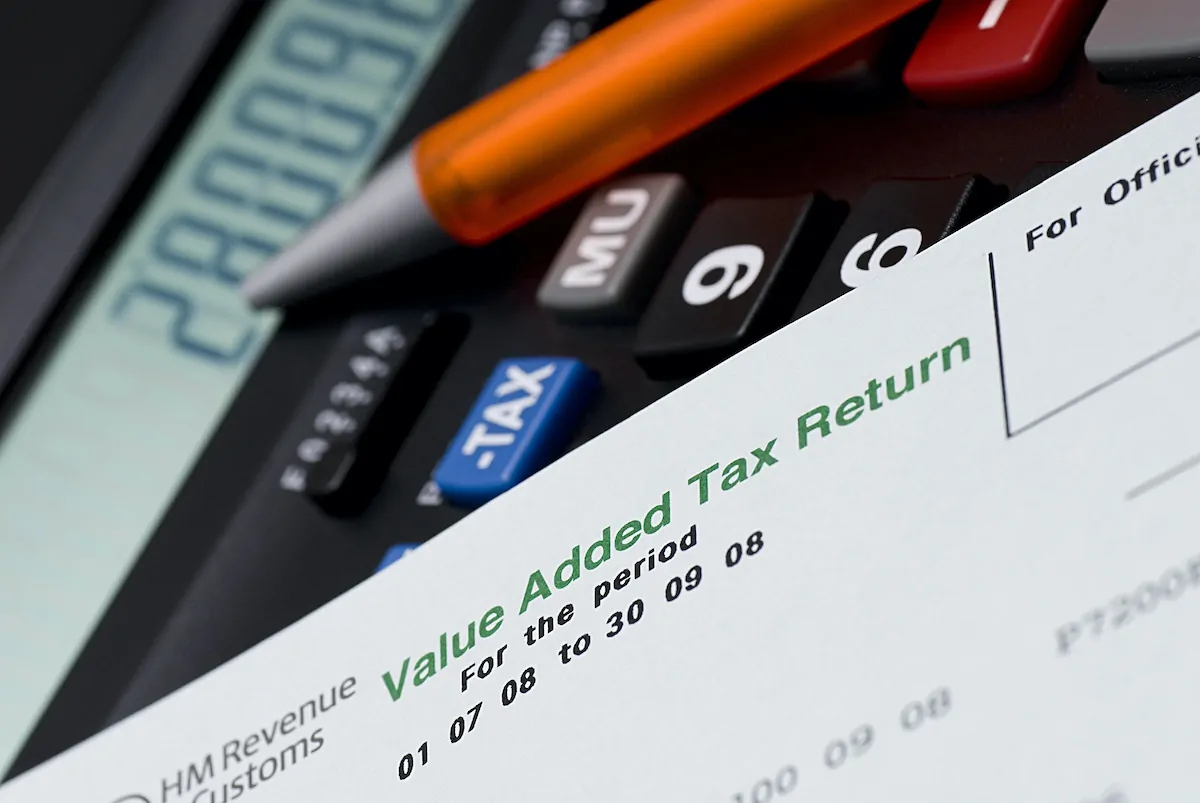

Brexit VAT

The European Council’s VAT Directive requires EU member states to comply with its VAT framework when setting Value Added Tax rates. However, the directive also offers them a degree of freedom when it comes to defining the exact number and level of VAT rates, provided they comply with the following two rules:

- A standard rate of VAT - the rate that member states have to apply to all non-exempt goods and services (Article 96 of the VAT Directive). The standard rate must be no less than 15%, but there is no maximum.

- One or two reduced rates of VAT – in addition to the standard rate EU countries can choose to set one or two reduced rates, but they can only be applied to certain goods and services (those listed in Annex III of the VAT Directive), and the rates must not be lower than 5% or higher than 15%.

After leaving the European Union the British government would not be bound by the EU’s VAT Directive, and this would still be the case even if the Article 50 negotiations resulted in the UK joining the EEA under the Norway model (which is the most sensible and plausible proposal for Britain’s exit).

Britain would have the power to cut its VAT rates below 15% (or even below 5%) in order to stimulate the economy, and the goods and services that receive special VAT treatment would be determined by Westminster rather than Brussels. This strategy has been adopted by Switzerland and Liechtenstein, which both have a standard VAT rate of 8% and reduced rates of 2.5% and 3.8%. Of course, there’s no guarantee the British government would do the same, particularly considering it’s likely to need all the tax revenue it can get.

Brexit Capital Gains Tax

Capital Gains Tax is not harmonised across the EU, and is classed as "out of scope" when it comes to the ‘European Union withholding tax’. As such, any change to Britain’s Capital Gains Tax in the months and years ahead is likely to be based on the UK government’s efforts to increase tax revenues and/or stimulate economic growth in the UK.

Budget 2016 saw a significant change to Britain’s Capital Gains Tax rates, when it was announced that the 18% rate of CGT on chargeable gains would be reduced to just 10% from 6th April 2016, while the 28% rate was cut to 20%. It remains to be seen whether David Cameron’s replacement will undo those cuts or keep them as they are.

Brexit Customs duties

Under the European Union Customs Union all the current 28 member states of the EU, plus Andorra, Monaco, San Marino and Turkey, allow the free movement of goods without imposing customs duties. The EUCU also requires the same countries to impose a common external tariff on any goods entering the union from a country outside it.

Whether the UK will remain part of this customs union will depend on how negotiations proceed after Article 50 is invoked. It’s possible Britain might become an EEA member by joining the European Free Trade Association, which would allow the free movement of goods between EFTA members (Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland, plus the UK) without imposing customs tariffs.

However, membership of EFTA wouldn’t automatically offer Britain access to the free movement of goods within the much larger EU, and it’s possible (and, according to some economists, very likely) that some customs tariffs could be imposed on British exports by the EU (and, equally, on EU imports by the UK).