1,000 UK restaurants go bust in 2017 – is it just the beginning?

26 Mar 2018The number of UK restaurants going bust jumped by a fifth last year as major chains came under pressure from rising costs and competition amid a squeeze on consumer spending.

There were nearly 1,000 insolvencies across the restaurant industry in 2017 compared with 825 the year before, according to law firm Moore Stephens.

Notable brands include the Handmade Burger Co chain and Liverpool-based Viva Brazil Steakhouse which was later bought out in a rescue deal.

The trend has continued into 2018 with Jamie’s Italian planning to close 12 of its 37 UK branches as part of a rescue attempt, while burger chain Byron and Italian outlet Strada are both closing a third their restaurants in a similar move.

After entering administration late last year, London-based chain Square Pie closed off all five of its existing premises in early February as they failed to find a buyer for the restaurant side of the business.It is likely that pressure on the restaurant sector is now hitting even the biggest names on the high street.

The jump in insolvencies over the last year demonstrates just how tough the current economic conditions are for the restaurant trade.

As a small business accountant, we are dedicated to fully understanding how the business environment impacting some of the big names above can also impact the smaller companies in our economy.

For this reason, we have to question if the insolvency issue taking the restaurant industry by storm is limited solely to those who operate in the sector, or should other businesses be concerned, too?

Characteristics of a company at risk of crisis

What we know about the restaurants who make up the sector in the UK is that while they have a fixed premises and a full commitment to their staff, there is no way they can guarantee generating cash or being in receipt of recurring income.

Instead, they rely solely on customer loyalty to come through their doors and pay for their food.

But what other types of business operate in a similar scenario?

Well, retail for one. Like restaurants, they have a fixed premises to be paid for, and in the same way restaurants need staff to cook and serve food, a lot retailers rely on their staff to man the floors, run the tills and keep the changing rooms in order.

In addition, retail buy stock in bulk with the hope of it selling, just like restaurants do with their ingredients. If anything, retailers are left in an even greater limbo with regards to stock, buying up goods to supply customers for months in advance, rather than days as is the case with restaurants.

Furthermore, it has been no secret over the past few moths that economic uncertainty surrounding Brexit has put luxury items into perspective for many of the UK’s shoppers. As consumers become more reluctant to spend on nice-to-haves, are the likes of retailers and restaurants put in a compromised position?

Overall, it could quite be the case that a little disruption in a retailer’s overheads could see their profit margins swing in a negative direction. Could that disruption be the new minimum wage which comes into effect in April of this year? In simple terms, higher wages would result in higher costs - can companies with the above characteristics that cost hike?

Challenges for traditionally lower-paying industries

The rise in the legal minimum wage and low availability of staff prompted by fewer Europeans coming to the UK in the wake of the Brexit vote have increased the challenges.

Previously, migrants from Europe would have, in some cases, been a cheaper source of labour for certain industries, but the fall in the value of the pound has made potential take-home pay less attractive for European workers and increased the price of food and other essentials for restaurateurs.

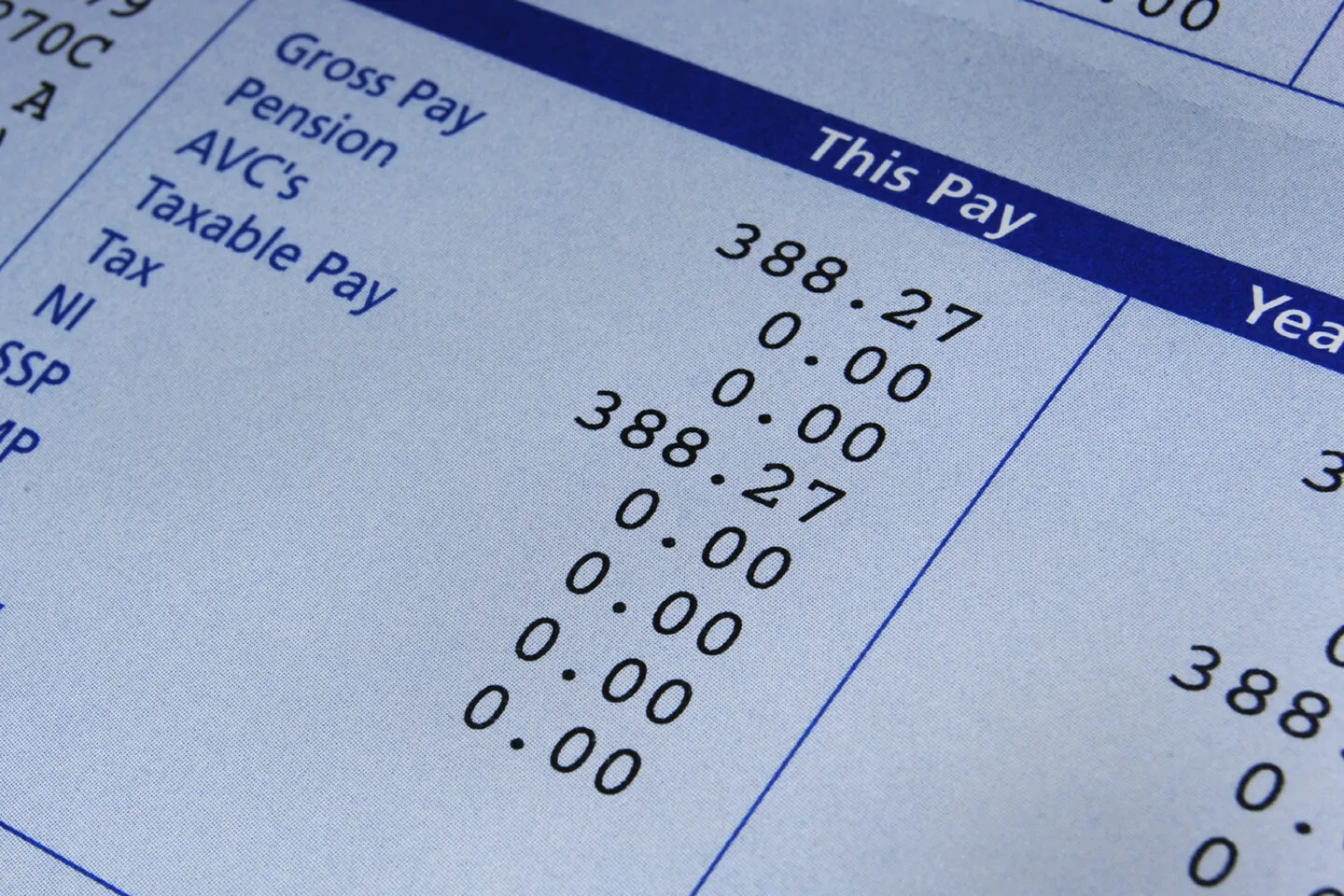

The Low Pay Commission estimates that there were 1.9 million jobs paid at or below the NMW in April 2017, around 6.7% of all employee jobs. This compares to 1.5 million jobs paid at or below the NMW in 2015, before the introduction of the National Living Wage.

The coverage of the NMW is expected to increase to 3.4 million employees by 2020 as the National Living Wage moves towards its 2020 target.

Jobs paid around the minimum wage are concentrated within a small number of low paying occupat ions. The Low Pay Commission estimates that half of all jobs paying at or below the minimum wage are in retail, hospitality and cleaning & maintenance occupations.

Trend in minimum wage jobs

The number of jobs paid at or below the minimum wage has increased since it was first introduced in 1999. It is estimated that around 1.1 million more people are in jobs paid at or below their relevant minimum wage rate in 2017 than in 1999.

The percentage of employee jobs paid at or below the minimum wage varies across countries and regions of the UK. Coverage (minimum wage jobs as a proportion of all jobs) is lowest in London and the South East at 4-5%, and highest in Northern Ireland at 12%.

Minimum wage jobs

The Low Pay Commission estimates the number of “minimum wage jobs”, defined as jobs paying up to five pence above the appropriate minimum wage rate (for all age groups, not just people aged 25 and over).

They estimate that 1.9 million employee jobs (6.7% of all employee jobs) were paid at or below the relevant National Minimum Wage rate in April 2017. The LPC forecasts this will increase to 3.4 million in 2020.

Occupations

Minimum wage jobs are concentrated in a relatively small number of occupations. Half of all minimum wage jobs are in just three occupation groups: retail, hospitality and cleaning & maintenance.

Although the number of people paid at the NMW in a particular occupation may be small, this can represent a large proportion of employees in that occupation.

For example, there are approximately 304,000 jobs in Retail occupations paid at the National Living Wage, but this represented almost 20% of people aged 25 and over working in those occupations.

In the same vein, there are approximately 242,000 jobs in Hospitality occupations paid at the National Living Wage, but this represented almost 31% of people aged 25 and over working in those occupations.

These are just two examples of several sectors who have a sizeable proportion of minimum wage employees. Accounts and Legal intend to release full statistics and in-depth data analysis in the near future.

In conclusion, it appears the insolvency crisis may be about to spread beyond the restaurants of the UK, partially driven by the perfect storm of company characteristics and the employees on their payroll.